Hello all! This is just an extra blog post that I promised Julie I'd write long ago, because I was (and still am) extremely embarrassed that I wasn't able to discuss Rappaccini's Daughter back in week 7 due to the fact that I hadn't read it. Well, now I have read it! After choosing another Hawthorne piece for essay 3 of the midterm, I have decided to compare the two texts in order to highlight key themes in Hawthorne's work. There are definite similarities found in Hawthorne's texts"The Birthmark" and "Rappaccini's Daughter," and both stories include strong arguments that man does not have the right or the power to mess with Nature.

In "Rappaccini's Daughter," There is an act of worship regarding Nature that cannot be overlooked. Within the opening of the story, the author establishes that Giovanni "found no better occupation than to look down into the garden beneath his window," and upon his gift of the plant to Beatrice, she promises "Yes, my sister, my splendor; it shall be Beatrice's task to nurse and serve thee; and thou shalt reward her with thy kisses and perfume breath, which to her is as the breath of life!" Sure, she is intimate with the plants because she has been severly effected by them physically, but both of these characters posses great respect for these plants, and it is shocking how this respect later evolves into a blatant abuse of the plants when this very science was meant only to develop medicines for the good of mankind, which should Nature in it's position of power. Later, readers discover that Beatrice has indeed fallen victim to her father's experiments, "the effect of my father's fatal love of science-- which estranged me from all society of my kind." She is poisonous, and Giovanni discovers that his exposure to the strange plants has made him poisonous as well. I think the death of Beatrice indeed teaches Rappaccini a lesson in leaving Nature alone.

A similar tale is told in Hawthorne's "The Birthmark," in which the main character Aylmer is a scientist who's sole desire has become the removal of his wife Georgianna's unsightly birthmark:

“What will be my triumph when I shall have corrected what Nature left imperfect in her fairest work!” Aylmer is extremely confident in his abilities to undue such a permanent blemish, and breaks down Georgianna's spirit to the point where she gives in to his wishes to remove it. It is as if she is teetering on the final thread of life when she exclaims, “Danger is nothing to me; for life, while this hateful mark makes me the object of your horror and disgust, -- life is a burden which I would fling down with joy. Either remove this dreadful hand, or take my wretched life!” He finally manipulated her to the point of no return- she doesn't care what the cost is, she just wants the dreadful mark gone. The whole point of the story, however, is how defiant acts against Nature never end well, and she of course dies on the operating table.

Hawthorne's theme of science's fatal quest to defy Nature is evident in both of these stories, each ending tragically. It seems that Hawthorne chooses the most innocent to die in order to teach lessons to those who abandoned the worship of Nature in the first place, which is an important element to note. So basically, think twice before the next time you litter.

Friday, March 26, 2010

Thursday, March 25, 2010

The Revolt of the White Heron- A Voice for Women

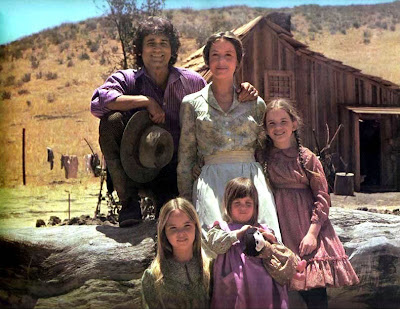

For those of you who grew up not knowing Laura Ingalls and her family, well, here they are! The barn in the background of this picture is not unlike the very barn I had imagined while reading Freeman's "The Revolt of Mother."

For those of you who grew up not knowing Laura Ingalls and her family, well, here they are! The barn in the background of this picture is not unlike the very barn I had imagined while reading Freeman's "The Revolt of Mother."On to Feminism. Both of the texts we read for today were clear arguments for women's rights, and I want to explore that idea further through examples that jumped out at me from the short stories themselves. While "The Revolt of Mother" was more of a warning to both the American government and society itself, Jewett's "A White Heron" promoted a woman's quest to discovering her own identity.

One of the moments in "The Revolt of Mother" that stuck out to me in particular was when Mother and her daughter were doing chores together, "Her mother scrubbed a dish fiercely. 'You ain't found out yet we're women-folks, Nanny Penn,' said she. 'You ain't seen enough of men-folks yet to. One of these days you'll find it out, an' then you'll know that we know only what men-folks think we do, so far as any use of it goes, an' how we'd ought to reckon men-folks in with Providence, an' not complain of what they do any more than we do of the weather.'" From just the simple act of scrubbing a dish fiercely, the reader is clued into the fact that this woman might not like the way things are, but she is grittin' her teeth and submitting anyways. Mother is using this conversation with her daughter to educate and warn her of the societal rules. Wives are not to question their husbands, and women are viewed on a lower level than men. Mother's own son had been aware of the building of the barn (FOR THREE MONTHS!) and didn't feel it necessary to clue his mother in on it. Even though this act would appear to be dishonest and sneaky in modern times, back then it was normal practice to make big decisions that concerning the welfare of the entire family without consulting the wife. Mother was fully aware of her duties.

We all know that this situation only lasted 40 years (ONLY), and eventually Mother snapped and took matters into her own hands. After a lifetime of servitude to a man who did not seem to value her opinion or desires, she made a life changing decision that could have been disastrous- Instead, Father found the error of his ways and recognized that her needs were just as important as his own. How ironic that the country was on the cusp of the Women's Suffrage movement, not quite ready to take the plunge, yet teetering on the edge of equality.

Jewett took a more subtle approach in "A White Heron," allowing the process of moral dilemma be the turning point for young Sylvia. Rather than revolt vocally against the hunter-man, she made an internal choice to omit information that would have allowed him to complete his mission of finding a white heron.

The first point I would like to make about the young man is that he treats these women just the same as the woman in Freeman's text. Upon his arrival, he was searching for a place to stay, and though it appeared to be a simple request, his demanding demeanor is a bit shocking (to me).

"Put me anywhere you like," he said. "I must be off early in the morning, before day; but I am very hungry, indeed. You can give me some milk at any rate, that's plain." It's not that he's unkind, and I realize that customs were different back then, but I do ask: would he have spoken this way if Sylvia had been living with her grandfather and not her grandmother?

As Sylvia embarks on her journey of enlightenment, she questioned his motives secretly: "Sylvia would have liked him vastly better without his gun; she could not understand why he killed the very birds he seemed to like so much." Though she was captivated by the young man, she had enough awareness to wonder whether his purposes were moral. She is very unlike Mother in her ultimate decision to remain silent, as she does not directly confront the hunter.

Are the messages the same in both of the texts? I would argue that they are in fact both in favor of feminism, however the push for gender equality is definitely more apparent in "The Revolt of Mother." One aspect of the story to consider is how long it took Mother to do what she did. She withstood the inequality for 40 years before she said something. Perhaps if she had experienced what Sylvia had when coming of age, she might have been enlightened enough and strong enough to realize her value sooner. Through "A White Heron," many messages can be conveyed concerning equality among all peoples, especially when Capitalist gains are in the picture.

So the final question is: money or piece of mind? I'll let you decide.

Thursday, March 11, 2010

A Victorian War?

"The Crimean is today less compelling, and the generic conventions Fenton used to naturalize the scenes of war seem contrived or empty. The very conventions that make these photographs difficult for us to read, were, however, what made them appealing to a Victorian audience that desired to possess history." The Crimean photograph above is a perfect example of what Natalie Houston was talking about in her article, as if definitely appears to be staged in some way. I mean, the gentleman pictured in Fenton's "The Artist's Van" is sitting perfectly stoic on a wagon that is being led my nothing. So he's just sittin' there, staring blankly into space. Sure, it's artistic, and I'm sure at the time it was taken that this type of photograph was all the rage, but I definitely feel the loss that Houston discussed in her article. If the audience isn't able to decipher the purpose of the picture, then how are they able to appreciate it?

Houston claims that "By focusing on the officers and portraying them in this stylized manner, the real hardships faced by the troops are minimized, suggesting perhaps Fenton’s political acquiescence to his Royal sponsor. " I get that he couldn't get a clear shot if people didn't stand still, but the fact that a good chunk of the people in the photos are in clean, pressed uniforms doesn't make it seem like there's a war going on. His style is extremely Victorian, very formal, and while he at least gives recognition to those who were there, the rules that prohibited him ends up devaluing the experience of the soldiers. By not being able to capture images of dead bodies (as horrible as that sounds) and technology restricting his ability to capture battle scenes, without a written explanation of things we would never really get the whole picture.

Houston points out that "The primary function of Fenton’s photographs was to memorialize and record that which was already known, rather than to present something new." This technology was so new, they knew the limits. They were there simply to record, to capture even the smallest piece of the souls of the men who were there, and now we have teh history to prove it. Are they staged? For sure. Are they realistic to the settings? Not really. But did each of the men photographed serve their country? Absolutely. And I suppose that's what counts.

Thursday, March 4, 2010

Whitman is sportin' the Levi's

You know, I'm just going to start off by saying how BRILLIANT I think it is that Levi's used Walt Whitman's poetry and even his own voice in order to promote their brand name. It is clear that Whitman had a great love for his country, and I feel that love is excellently put to use for America's advertisements. McCracken quotes Whitman:"The proof of a poet is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it." Levi's has always been associated with America and the working man, it is the oldest, most trusted brand, and the men who shaped our lands and worked our fields wore them. With all things considered, the only person better suited to be a spokesperson for Levi's would be John Muir. . . (That's for you, Julie!).

In Leaves of Grass, Whitman argues, "Come to us on equal terms, Only then can you understand us, We are no better than you, What we enclose you enclose, What we enjoy you may enjoy." Who are we kidding!! It's like Gold points out, "Advertising has taken up what Whitman thought was the poet’s job." And it's true! I really felt like the article celebrated any involvement that the Levi's campaign had with Whitman. Just from my own perspective, why wouldn't you want to include someone who contributed so much to America's literary past? Not only are they helping to promote his standing legend, but they are revisiting the roots that Whitman reminded America about in the first place. You just can't go wrong when you incorporate things that people should already know (but probably don't) into something that they can see in their everyday lives. Too much of our history is lost on the younger generations as it is.

Poets were the voice of the past. Is it sad and disappointing that advertisement is the great influencer of the future? Of the present? I kind of think so.

In Leaves of Grass, Whitman argues, "Come to us on equal terms, Only then can you understand us, We are no better than you, What we enclose you enclose, What we enjoy you may enjoy." Who are we kidding!! It's like Gold points out, "Advertising has taken up what Whitman thought was the poet’s job." And it's true! I really felt like the article celebrated any involvement that the Levi's campaign had with Whitman. Just from my own perspective, why wouldn't you want to include someone who contributed so much to America's literary past? Not only are they helping to promote his standing legend, but they are revisiting the roots that Whitman reminded America about in the first place. You just can't go wrong when you incorporate things that people should already know (but probably don't) into something that they can see in their everyday lives. Too much of our history is lost on the younger generations as it is.

Poets were the voice of the past. Is it sad and disappointing that advertisement is the great influencer of the future? Of the present? I kind of think so.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)