Well, we've finally made it here once again! After careful deliberation, I have decided to focus on the women of some of the texts that we've read. Here's what I am thinking and why.

Texts to be discussed:

-Margaret Fuller's "The Great Debate" (Transcendentalism)

-Freeman's "The Revolt of Mother" (Local Color and Regionalism)

-Jewett's "A White Heron" (Local Color and Regionalism)

-Henry James' Daisy Miller (Realism)

-Hawthorne's "The Birthmark" (Dark Romanticism)

Tentative thesis:

"Some women represented in the fictional works listed above are defined by the societal roles placed on the female sex, and are often victims of the stories because of this reality. However, the few women who represent independent thinking convey a positive message of individuality that actually encourages the women of the present society to embrace their womanhood, presenting a call to action for equality. Through the examples of these fictional women, female readers are encouraged to claim and fight for their individual identity, and coupled with women's non-fictional works such as Fuller's Essay "The Great Debate," the movement of women's suffrage was inevitable. Present day society would not be the same had texts like these not paved the way, illustrating that it was in fact possible for women to break the mold that had previously confined them."

Why I chose these works:

I chose Daisy Miller because at the time, she was considered the stereotype of American women. Her biggest concern was not her studies or a possible career, it was partying and fooling around until eventually a marriage to an upstanding gentleman presented itself. Because of the lack of convention and avenues for women to rise above preconditioned roles, the purpose of a woman's life was pretty much exemplified through Daisy's character. It was because she didn't have other options that she chose to act the way that she did- she was bored with her life, and all she cared about was looking pretty and flirting. Her tragic end in death only makes an example of her, showing that women who are confined by the stereotypes placed by men will search for happiness elsewhere, and that elsewhere just might include unconventional methods of man-hunting. She never got the chance to explore her options and discover who she really was.

I chose "The Birthmark" for similar reasons, only this story is more of a display of a husband's control over his wife. Georgiana had never been so mortified by her birthmark until she got married and her husband admitted his repulsion of it. Her feelings were so manipulated by him that it didn't even take much effort on his part to convince her to allow him to try and remove it. She is completely his property, and doesn't feel valued in her natural state- her identity is completely enveloped in being Aylmer's wife. Her fate ends in a tragic death also.

Things turn around a little bit for the the women in "The Revolt of Mother" and "A White Heron," as both women are able to make decisions for themselves that lead to freedom. In Freeman's text, Mother finally breaks free after 40 years of servitude to her family and of course, husband. She and her children might have been apprehensive or nervous about taking that final step and moving everything they owned to the barn, but Sarah stood her ground and didn't show any sign of weakness in her decision. Father completely gave in and didn't protest to her desires, and she was able to grasp everything she'd ever wanted in those 40 years- a new home.

In Jewett's "A White Heron," Sylvia encountered a specific moment in her youth in which she was able to make a choice that would change her life forever. She played host for a while, and yes she was indeed captivated by this new gentleman hunter, but in the end she was able to make her own moral decision about whether or not to tell him about the location of the white heron. She makes a choice that will later lead to other choices in her life, this incident was merely an avenue that would open thousands of doors down the road for her. Sylvia experienced a physical or intellectual awakening, which sadly some of the women in earlier texts never had the opportunity to have themselves. Though it was against common ideology for a woman to think solely for their own purposes, Sylvia embarks on a journey of self discovery here in this story.

The last text I would like to incorporate in my studies is Fuller's article "The Great Debate," simply because it was an extremely influential text of the time that addresses the very issues that the aforementioned texts present. She discusses women's constant dependence on men and how society has set it up specifically for women to be this way, and argues that marriage itself has presented this flaw in heterosexual relationships. She is clearly on the forefront or women's suffrage, and is in fact one of the first women to in fact pave the way for this entire movement. She argues that women are equally intelligent and capable of leading their own lives, which her own life exemplifies. I am going to end my paper discussing how each female character is either flawed because of a lack of independence from men or how they have benefited from this way of thinking, because her work is the only non-fiction work that we read addressing this topic, written with a beyond clear call to action that other texts might have hinted at, but non directly addressed.

So that's my proposal. Any other thoughts or ideas would be appreciated, as well as possible sources to support my work. Thank you!

Literature Thoughts

WSU 2012

Thursday, April 8, 2010

Saturday, April 3, 2010

In Muir's Footsteps. . .

"Azure skies and crystal waters find loving recognition, and few there be who would welcome the axe among mountain pines, or would care to apply any correction to the tones and costumes of mountain waterfalls."- John Muir, Wild Wool.

Girls in a Tree.

Daisy Miller Meets. . . .Girls Gone Wild?

I just have to say for all of you people who finished The Coquette earlier this week, are these two stories not eerily similar???

Moving on. I can see how Americans might have been offended back in the day for the flirtatious Daisy Miller being the supposed representative for the typical American girl, loose and unrefined. Back then, world travel wasn't as accessible of an endeavour as it is today, and anything read in print was a big deal and were taken seriously.

But come on!!! Just because one little book says it's so does not make it the truth- and Daisy Miller is a fictional work! Henry James is not claiming that all girls are like Miss Miller!(but if we find out on Tuesday that he really did think this, ignore the aforementioned statement.) Does anyone remember what happened when Borat made his way across America? Hello!!! He thought TONS of things were true about American girls because he had seen real live footage of drunk college chicas taking off their clothes in Girls Gone Wild videos! I mean seriously! The main point I'm trying to make here is that readers should always analyze the texts they are reading critically, and understand that the arguments being made may in fact be debatable.

I think the focal point of the story( and I guess we'll find out if I'm grasping at straws on Tuesday) is foreign relations and the fascination of other cultures. Winterbourne is constantly making pro-American statements such as "American girls are the best girls" and "American's candy's the best candy" (6). Well come on, you know it's true! And even Daisy makes comments here and there indicating that her main interest in any country or culture is its society: "The society's extremely select [in Rome]. There are all kinds- English, Germans, and Italians. I think I like the English the best. I like their style of conversation. But there are some lovely Americans. I never saw anything so hospitable" (39). Both Daisy and Winterbourne are infatuated with other cultures, and the entire novel illustrates how one is easily swept up in this idea of racial pride.

The most important thing that Daisy says, however, is in her heated response to Mrs. Walker's exclamations that she was ruining her reputation by taking long walks in the dark alone with a strange man (well, come on now, who are we kidding. . . she kind of was- no matter what society she was a part of). Nevertheless, she argues: "The young ladies of this country have a dreadfully poky time of it [entering relationships with members of the opposite sex], so far as I can learn; I don't see why I should change my habits for them" (49). She admits to being a flirt and attracted to men of foreign lands, and she refuses to abandon her "dating style" for the sake of reputation., to which her companion responds, "Flirting is purely and American custom; it doesn't exist here" (50).

So there you go. Daisy feels confined by all the rules of each society she tries to become a part of (though society is all that she lives for), yet she is unwilling to relinquish her now taboo act that we call "the flirt." Doesn't really matter what she decided to do or didn't decide to do, because in the end she DIES and so her flirtatious, dare I say, coquettish days are abruptly ended. (Again, similarities are presented between this and The Coquette). Henry James couldn't think of a better way to put an end to the dreadful flirting- he just had to off her in one page. ONE PAGE. She was so evil, wanting to be free from social pressures. I guess that flirtatious American bitch really got what she deserved.

Friday, March 26, 2010

Hawthorne: A Brief Comparative Analyisis (And a quick fun bounce back into Dark Romanicism!)

Hello all! This is just an extra blog post that I promised Julie I'd write long ago, because I was (and still am) extremely embarrassed that I wasn't able to discuss Rappaccini's Daughter back in week 7 due to the fact that I hadn't read it. Well, now I have read it! After choosing another Hawthorne piece for essay 3 of the midterm, I have decided to compare the two texts in order to highlight key themes in Hawthorne's work. There are definite similarities found in Hawthorne's texts"The Birthmark" and "Rappaccini's Daughter," and both stories include strong arguments that man does not have the right or the power to mess with Nature.

In "Rappaccini's Daughter," There is an act of worship regarding Nature that cannot be overlooked. Within the opening of the story, the author establishes that Giovanni "found no better occupation than to look down into the garden beneath his window," and upon his gift of the plant to Beatrice, she promises "Yes, my sister, my splendor; it shall be Beatrice's task to nurse and serve thee; and thou shalt reward her with thy kisses and perfume breath, which to her is as the breath of life!" Sure, she is intimate with the plants because she has been severly effected by them physically, but both of these characters posses great respect for these plants, and it is shocking how this respect later evolves into a blatant abuse of the plants when this very science was meant only to develop medicines for the good of mankind, which should Nature in it's position of power. Later, readers discover that Beatrice has indeed fallen victim to her father's experiments, "the effect of my father's fatal love of science-- which estranged me from all society of my kind." She is poisonous, and Giovanni discovers that his exposure to the strange plants has made him poisonous as well. I think the death of Beatrice indeed teaches Rappaccini a lesson in leaving Nature alone.

A similar tale is told in Hawthorne's "The Birthmark," in which the main character Aylmer is a scientist who's sole desire has become the removal of his wife Georgianna's unsightly birthmark:

“What will be my triumph when I shall have corrected what Nature left imperfect in her fairest work!” Aylmer is extremely confident in his abilities to undue such a permanent blemish, and breaks down Georgianna's spirit to the point where she gives in to his wishes to remove it. It is as if she is teetering on the final thread of life when she exclaims, “Danger is nothing to me; for life, while this hateful mark makes me the object of your horror and disgust, -- life is a burden which I would fling down with joy. Either remove this dreadful hand, or take my wretched life!” He finally manipulated her to the point of no return- she doesn't care what the cost is, she just wants the dreadful mark gone. The whole point of the story, however, is how defiant acts against Nature never end well, and she of course dies on the operating table.

Hawthorne's theme of science's fatal quest to defy Nature is evident in both of these stories, each ending tragically. It seems that Hawthorne chooses the most innocent to die in order to teach lessons to those who abandoned the worship of Nature in the first place, which is an important element to note. So basically, think twice before the next time you litter.

In "Rappaccini's Daughter," There is an act of worship regarding Nature that cannot be overlooked. Within the opening of the story, the author establishes that Giovanni "found no better occupation than to look down into the garden beneath his window," and upon his gift of the plant to Beatrice, she promises "Yes, my sister, my splendor; it shall be Beatrice's task to nurse and serve thee; and thou shalt reward her with thy kisses and perfume breath, which to her is as the breath of life!" Sure, she is intimate with the plants because she has been severly effected by them physically, but both of these characters posses great respect for these plants, and it is shocking how this respect later evolves into a blatant abuse of the plants when this very science was meant only to develop medicines for the good of mankind, which should Nature in it's position of power. Later, readers discover that Beatrice has indeed fallen victim to her father's experiments, "the effect of my father's fatal love of science-- which estranged me from all society of my kind." She is poisonous, and Giovanni discovers that his exposure to the strange plants has made him poisonous as well. I think the death of Beatrice indeed teaches Rappaccini a lesson in leaving Nature alone.

A similar tale is told in Hawthorne's "The Birthmark," in which the main character Aylmer is a scientist who's sole desire has become the removal of his wife Georgianna's unsightly birthmark:

“What will be my triumph when I shall have corrected what Nature left imperfect in her fairest work!” Aylmer is extremely confident in his abilities to undue such a permanent blemish, and breaks down Georgianna's spirit to the point where she gives in to his wishes to remove it. It is as if she is teetering on the final thread of life when she exclaims, “Danger is nothing to me; for life, while this hateful mark makes me the object of your horror and disgust, -- life is a burden which I would fling down with joy. Either remove this dreadful hand, or take my wretched life!” He finally manipulated her to the point of no return- she doesn't care what the cost is, she just wants the dreadful mark gone. The whole point of the story, however, is how defiant acts against Nature never end well, and she of course dies on the operating table.

Hawthorne's theme of science's fatal quest to defy Nature is evident in both of these stories, each ending tragically. It seems that Hawthorne chooses the most innocent to die in order to teach lessons to those who abandoned the worship of Nature in the first place, which is an important element to note. So basically, think twice before the next time you litter.

Thursday, March 25, 2010

The Revolt of the White Heron- A Voice for Women

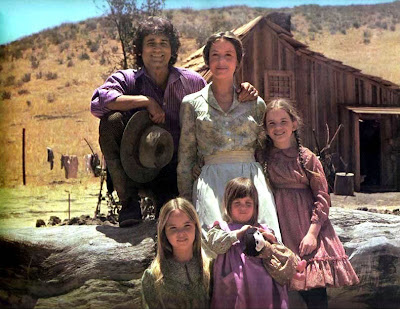

For those of you who grew up not knowing Laura Ingalls and her family, well, here they are! The barn in the background of this picture is not unlike the very barn I had imagined while reading Freeman's "The Revolt of Mother."

For those of you who grew up not knowing Laura Ingalls and her family, well, here they are! The barn in the background of this picture is not unlike the very barn I had imagined while reading Freeman's "The Revolt of Mother."On to Feminism. Both of the texts we read for today were clear arguments for women's rights, and I want to explore that idea further through examples that jumped out at me from the short stories themselves. While "The Revolt of Mother" was more of a warning to both the American government and society itself, Jewett's "A White Heron" promoted a woman's quest to discovering her own identity.

One of the moments in "The Revolt of Mother" that stuck out to me in particular was when Mother and her daughter were doing chores together, "Her mother scrubbed a dish fiercely. 'You ain't found out yet we're women-folks, Nanny Penn,' said she. 'You ain't seen enough of men-folks yet to. One of these days you'll find it out, an' then you'll know that we know only what men-folks think we do, so far as any use of it goes, an' how we'd ought to reckon men-folks in with Providence, an' not complain of what they do any more than we do of the weather.'" From just the simple act of scrubbing a dish fiercely, the reader is clued into the fact that this woman might not like the way things are, but she is grittin' her teeth and submitting anyways. Mother is using this conversation with her daughter to educate and warn her of the societal rules. Wives are not to question their husbands, and women are viewed on a lower level than men. Mother's own son had been aware of the building of the barn (FOR THREE MONTHS!) and didn't feel it necessary to clue his mother in on it. Even though this act would appear to be dishonest and sneaky in modern times, back then it was normal practice to make big decisions that concerning the welfare of the entire family without consulting the wife. Mother was fully aware of her duties.

We all know that this situation only lasted 40 years (ONLY), and eventually Mother snapped and took matters into her own hands. After a lifetime of servitude to a man who did not seem to value her opinion or desires, she made a life changing decision that could have been disastrous- Instead, Father found the error of his ways and recognized that her needs were just as important as his own. How ironic that the country was on the cusp of the Women's Suffrage movement, not quite ready to take the plunge, yet teetering on the edge of equality.

Jewett took a more subtle approach in "A White Heron," allowing the process of moral dilemma be the turning point for young Sylvia. Rather than revolt vocally against the hunter-man, she made an internal choice to omit information that would have allowed him to complete his mission of finding a white heron.

The first point I would like to make about the young man is that he treats these women just the same as the woman in Freeman's text. Upon his arrival, he was searching for a place to stay, and though it appeared to be a simple request, his demanding demeanor is a bit shocking (to me).

"Put me anywhere you like," he said. "I must be off early in the morning, before day; but I am very hungry, indeed. You can give me some milk at any rate, that's plain." It's not that he's unkind, and I realize that customs were different back then, but I do ask: would he have spoken this way if Sylvia had been living with her grandfather and not her grandmother?

As Sylvia embarks on her journey of enlightenment, she questioned his motives secretly: "Sylvia would have liked him vastly better without his gun; she could not understand why he killed the very birds he seemed to like so much." Though she was captivated by the young man, she had enough awareness to wonder whether his purposes were moral. She is very unlike Mother in her ultimate decision to remain silent, as she does not directly confront the hunter.

Are the messages the same in both of the texts? I would argue that they are in fact both in favor of feminism, however the push for gender equality is definitely more apparent in "The Revolt of Mother." One aspect of the story to consider is how long it took Mother to do what she did. She withstood the inequality for 40 years before she said something. Perhaps if she had experienced what Sylvia had when coming of age, she might have been enlightened enough and strong enough to realize her value sooner. Through "A White Heron," many messages can be conveyed concerning equality among all peoples, especially when Capitalist gains are in the picture.

So the final question is: money or piece of mind? I'll let you decide.

Thursday, March 11, 2010

A Victorian War?

"The Crimean is today less compelling, and the generic conventions Fenton used to naturalize the scenes of war seem contrived or empty. The very conventions that make these photographs difficult for us to read, were, however, what made them appealing to a Victorian audience that desired to possess history." The Crimean photograph above is a perfect example of what Natalie Houston was talking about in her article, as if definitely appears to be staged in some way. I mean, the gentleman pictured in Fenton's "The Artist's Van" is sitting perfectly stoic on a wagon that is being led my nothing. So he's just sittin' there, staring blankly into space. Sure, it's artistic, and I'm sure at the time it was taken that this type of photograph was all the rage, but I definitely feel the loss that Houston discussed in her article. If the audience isn't able to decipher the purpose of the picture, then how are they able to appreciate it?

Houston claims that "By focusing on the officers and portraying them in this stylized manner, the real hardships faced by the troops are minimized, suggesting perhaps Fenton’s political acquiescence to his Royal sponsor. " I get that he couldn't get a clear shot if people didn't stand still, but the fact that a good chunk of the people in the photos are in clean, pressed uniforms doesn't make it seem like there's a war going on. His style is extremely Victorian, very formal, and while he at least gives recognition to those who were there, the rules that prohibited him ends up devaluing the experience of the soldiers. By not being able to capture images of dead bodies (as horrible as that sounds) and technology restricting his ability to capture battle scenes, without a written explanation of things we would never really get the whole picture.

Houston points out that "The primary function of Fenton’s photographs was to memorialize and record that which was already known, rather than to present something new." This technology was so new, they knew the limits. They were there simply to record, to capture even the smallest piece of the souls of the men who were there, and now we have teh history to prove it. Are they staged? For sure. Are they realistic to the settings? Not really. But did each of the men photographed serve their country? Absolutely. And I suppose that's what counts.

Thursday, March 4, 2010

Whitman is sportin' the Levi's

You know, I'm just going to start off by saying how BRILLIANT I think it is that Levi's used Walt Whitman's poetry and even his own voice in order to promote their brand name. It is clear that Whitman had a great love for his country, and I feel that love is excellently put to use for America's advertisements. McCracken quotes Whitman:"The proof of a poet is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it." Levi's has always been associated with America and the working man, it is the oldest, most trusted brand, and the men who shaped our lands and worked our fields wore them. With all things considered, the only person better suited to be a spokesperson for Levi's would be John Muir. . . (That's for you, Julie!).

In Leaves of Grass, Whitman argues, "Come to us on equal terms, Only then can you understand us, We are no better than you, What we enclose you enclose, What we enjoy you may enjoy." Who are we kidding!! It's like Gold points out, "Advertising has taken up what Whitman thought was the poet’s job." And it's true! I really felt like the article celebrated any involvement that the Levi's campaign had with Whitman. Just from my own perspective, why wouldn't you want to include someone who contributed so much to America's literary past? Not only are they helping to promote his standing legend, but they are revisiting the roots that Whitman reminded America about in the first place. You just can't go wrong when you incorporate things that people should already know (but probably don't) into something that they can see in their everyday lives. Too much of our history is lost on the younger generations as it is.

Poets were the voice of the past. Is it sad and disappointing that advertisement is the great influencer of the future? Of the present? I kind of think so.

In Leaves of Grass, Whitman argues, "Come to us on equal terms, Only then can you understand us, We are no better than you, What we enclose you enclose, What we enjoy you may enjoy." Who are we kidding!! It's like Gold points out, "Advertising has taken up what Whitman thought was the poet’s job." And it's true! I really felt like the article celebrated any involvement that the Levi's campaign had with Whitman. Just from my own perspective, why wouldn't you want to include someone who contributed so much to America's literary past? Not only are they helping to promote his standing legend, but they are revisiting the roots that Whitman reminded America about in the first place. You just can't go wrong when you incorporate things that people should already know (but probably don't) into something that they can see in their everyday lives. Too much of our history is lost on the younger generations as it is.

Poets were the voice of the past. Is it sad and disappointing that advertisement is the great influencer of the future? Of the present? I kind of think so.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)